When Accidents Are Normal: Governing Tight, Complex Systems

Last month, we examined complex digital systems from a safe altitude. Guided by Meadows and Le Guin, we treated systems as evolving patterns of relationships rather than static machines. The practitioner’s task at that altitude was epistemic: improving feedback, resisting overconfidence, and designing governance that could adapt rather than deny change.

This month, we descend. If Meadows encourages humility in how we understand systems, Charles Perrow poses a more uncomfortable question for those who build and govern them: what happens when systems are designed so that serious failure stops being exceptional and becomes normal?

Perrow’s Normal Accidents: Living with High-Risk Technologies argues that in some systems, accidents are not the result of negligence, incompetence, or rare misfortune. They are structural consequences of system design. The problem shifts from epistemic limits (“we don’t fully understand the system”) to architectural inevitability (“the system will behave in uncontrollable ways”).

This essay uses Perrow’s theory, alongside Michael Crichton’s Airframe and two aviation accidents — China Eastern Airlines Flight 583 and Aeroflot Flight 593 — to examine a practical governance question relevant to digital platforms, laboratories, ICS networks, and other regulated environments:

If serious accidents are structurally inevitable in tightly coupled, interactively complex systems, what does responsible governance look like when we choose to build and operate them anyway?

The Pre-Perrow Mindset: Searching for the Last Link

Before the mid-1980s, dominant approaches to technological failure focused on discrete causes: faulty components, operator error, procedural violations, or external shocks. Safety engineering emphasized redundancy, fail-safe mechanisms, and compliance. When disasters occurred, investigations typically converged on the “last link”: the person or component closest in time to the failure.

This mindset persists. It appears in incident reports that close once a proximate cause is identified, and in governance cultures that treat accidents as deviations to be corrected rather than signals of systemic risk.

Perrow challenged this framing. In Normal Accidents (1984), he argued that some systems are structured in such a way that catastrophic failure cannot be prevented solely through better training or stricter procedures. In these systems, accidents arise from interactions among components, not isolated breakdowns. Responsibility, therefore, extends beyond the operational edge to designers, managers, regulators, and the architectural choices that shape the system.

Put simply:

- The last-link mindset asks: What went wrong, and who was responsible?

- Perrow asks: What made it possible for normal operations to combine into catastrophe?

Perrow’s Two Dangerous Properties

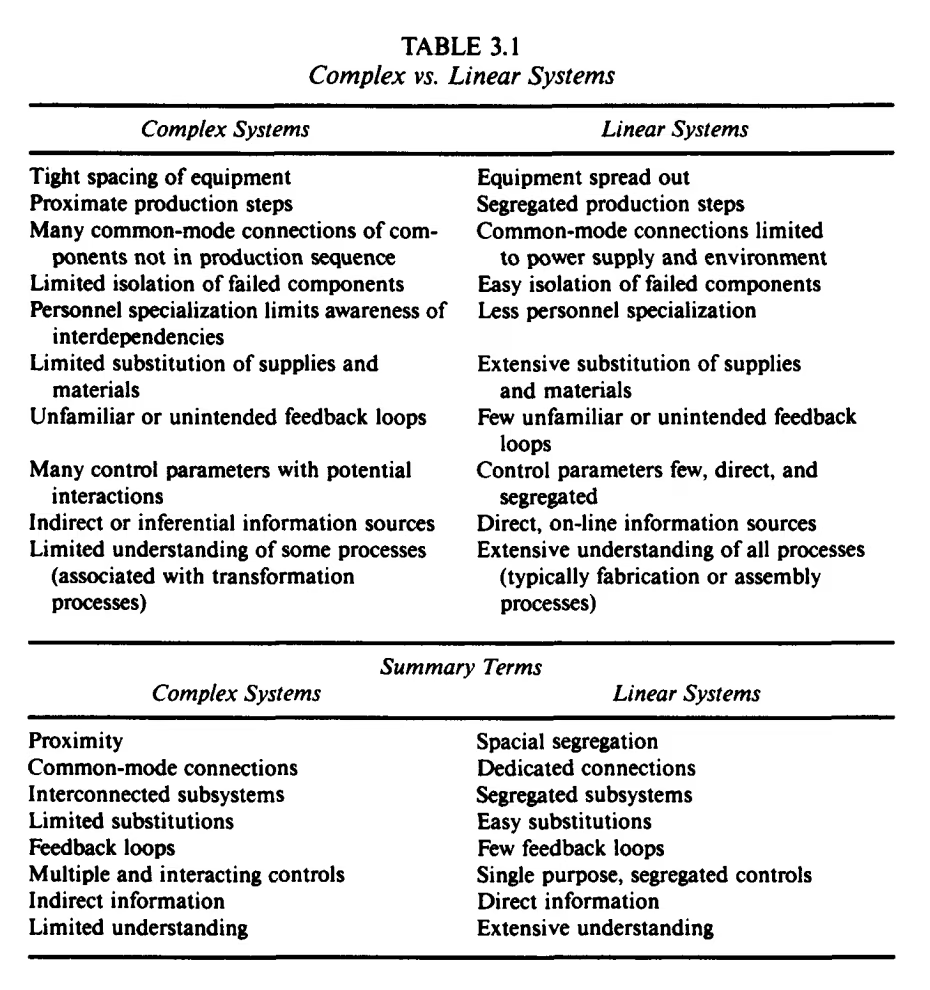

Perrow identifies two system properties that, when combined, make accidents “normal”:

Interactions “in which one component can interact with one or more other components outside the normal production sequence, either by design or not by design” (Perrow, 87–88).

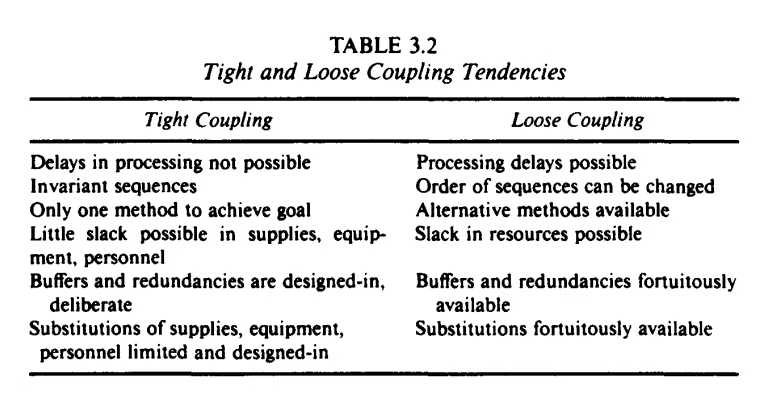

“A mechanical term meaning there is no slack or buffer or give between two items. What happens in one directly affects what happens in the other” (Perrow, 89).

When these properties coexist, and one of the system’s parts inevitably fails, they can produce a system accident (or normal accident), defined as:

an event that arises from the unanticipated interaction of multiple failures within a tightly coupled and interactively complex system, such that:

- Each failure may be minor, routine, or even the correct functioning of a component.

- No single failure can cause the accident.

- The failures combine in unexpected ways that the system’s design cannot reveal or predict.

- tight coupling prevents operators from intervening or halting the escalation.

When the above conditions occur together, accidents become structural features of the system — not anomalies, malfunctions, or operator errors, but inherent consequences of its architecture.

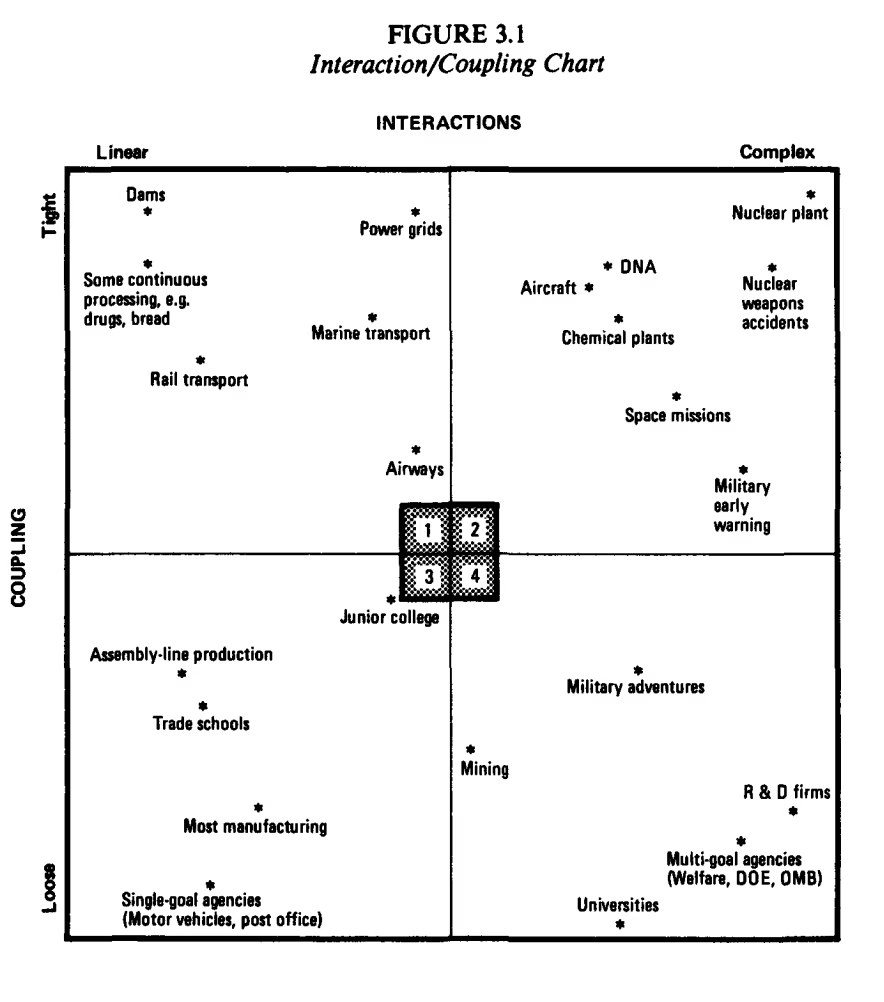

Below are two overviews (Table 3.1-3.2) taken from Normal Accidents to explain the concepts, and one matrix (Figure 3.1) that places different industries on the scale to explore their potential for ’normal accidents':

Why Aviation Makes Perrow’s Ideas Tangible

Aviation offers a clear illustration of Perrow’s argument. Commercial aircraft are engineered to the highest standards and operated by highly trained professionals within well-established regulatory regimes. Yet they remain among the most tightly coupled, complex systems operating today.

This is why Airframe and real aviation accidents are useful here — not as sensational stories, but as disciplined case material. They show how correct actions and well-designed components can combine into outcomes no one intends or fully understands.

Airframe: Narrative as Systems Analysis

Crichton’s Airframe shows what a system accident feels like from inside the system. The novel serves as an ethnography of a high-risk socio-technical environment under pressure, repeatedly staging the psychological and institutional demand for the last link, even when reality refuses to cooperate. Two instructive moments:

The demand for a single culprit.

Media and managerial pressure push toward a clean story because clean stories are governable stories. Perrow’s framework helps explain why that demand is structurally misaligned with complex reality.

Fragmented provenance under time pressure.

Information is not concealed so much as distributed across functions, systems, and incentives. Even with time, simulation, and expert reconstruction, the novel shows how difficult it is to model the internal states of complex systems. In complex operations, ignorance is often a result of organizational structure, not individual malice.

Airframe is not aviation ethnography, but it exposes a governance reflex: when the system’s causal mechanisms are too complex, institutions will often compress reality into a narrative they can act upon.

Two system Accidents in Practice

China Eastern Airlines Flight 583 (1993)

During cruise, a cockpit action inadvertently moved the flap/slat handle. Critically, investigators identified a design vulnerability: the handle could be moved inadvertently under certain conditions. That initiating event did not appear to be a “catastrophe”; it seemed like a tolerable deviation.

What followed illustrates Perrow’s world. The interaction among high-altitude aerodynamics, automation behavior, aircraft response dynamics, and cockpit interpretation produced violent oscillations. The crew faced ambiguous cues under time pressure, while the system’s coupling narrowed response windows. The danger emerged not from a single broken part, but from the interaction between design tolerances, human action, and tightly coupled dynamics.

A proximate cause narrative stops at “the handle was moved.” Perrow’s lens asks a harder question: Why was that action possible, and why did it cascade faster than the system could be understood and stabilized?

Aeroflot Flight 593 (1994)

In this case, a child applied slight pressure to the control yoke, partially disengaging the autopilot’s aileron channel. The system issued a subtle alert, but the crew, accustomed to more explicit warnings, did not register it. The aircraft entered a slow roll.

Crucially, the autopilot continued to manage other control axes, masking the disengagement and generating contradictory cues. As the bank angle increased, aerodynamic forces intensified, response windows narrowed, and recovery became impossible.

A conventional root cause investigation might stop at cockpit access. Perrow’s framework reveals something deeper: a system with hidden or partially legible modes, mixed automation states, and feedback patterns that can actively confuse skilled operators under stress.

The Structural Lesson for Governance

Perrow’s core claim is that in tightly coupled, complex systems, catastrophe often arises from ordinary actions interacting under constraint. The governance question, therefore, shifts from how to eliminate failure to:

- How do we govern systems where some failures will exceed our ability to interpret and intervene in time?

- How do we avoid turning governance into a storytelling exercise that produces closure without learning?

Responsible Governance: Practices That Mitigate system Accidents

Accepting inevitability does not imply resignation. It demands governance that prioritizes visibility, time to intervene, learning, and responsibility for system design.

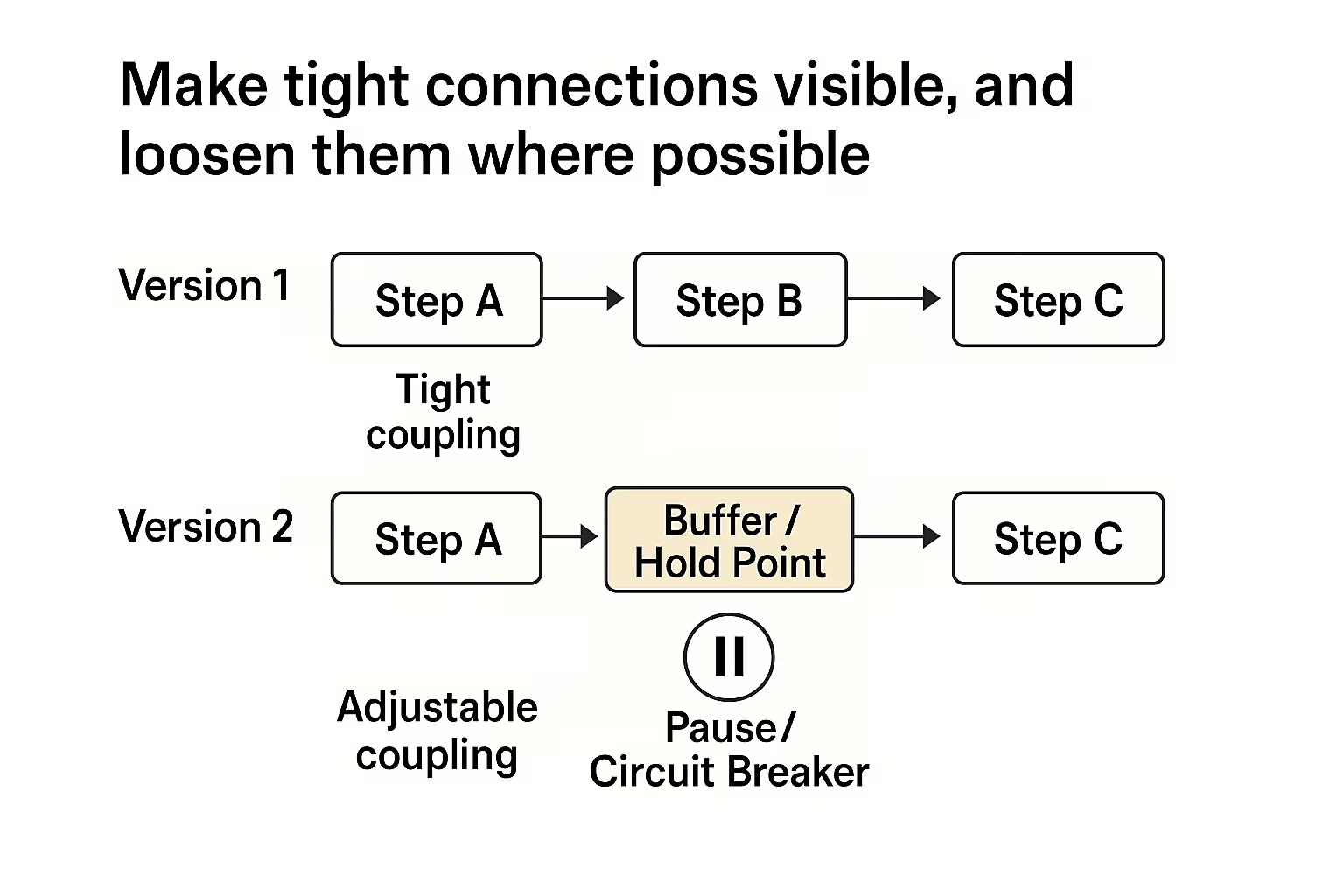

1) Make tight connections visible, and loosen them where possible

Governance should actively identify where processes are tightly coupled and ask where buffers, pause points, or circuit breakers can be introduced. Efficiency gains that eliminate slack should be treated as risk-increasing design decisions, not neutral optimizations.

In pharmaceutical manufacturing, continuous processing systems propagate deviations from raw material intake through to final product release with minimal opportunity for intervention. Real-time batch release decisions, enabled to reduce inventory costs, eliminate the buffer that previously allowed quality teams to pause and investigate ambiguous results before committing to the product.

NIS2’s supply chain security and business continuity requirements (Art. 21) assume organizations can identify and manage these dependencies. tight coupling means interventions in one domain cascade unpredictably into others.

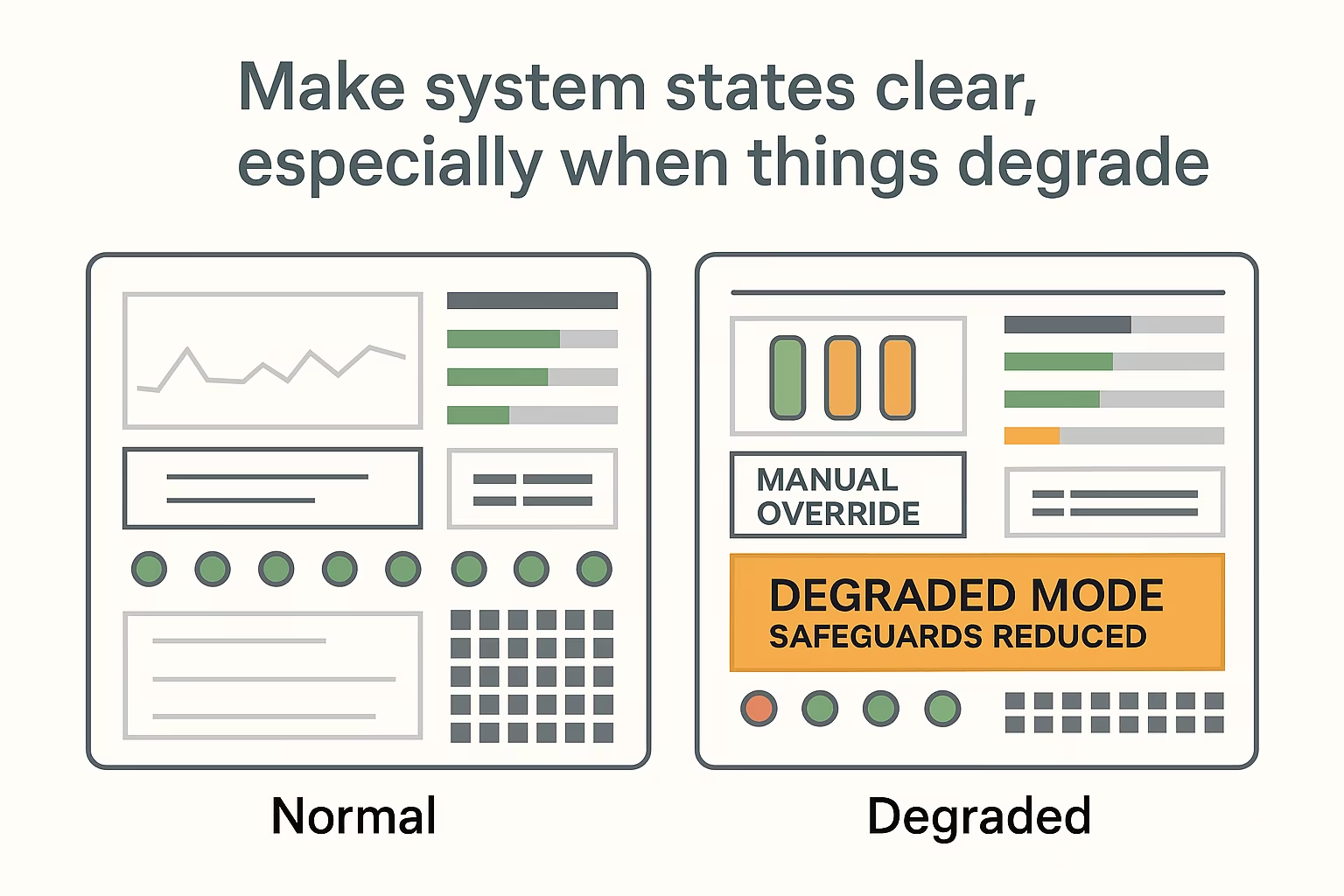

2) Make system states clear, especially when things degrade

Systems often continue to operate in a degraded state — with sensors overridden, alarms muted, or redundant backup processes in place — without making this obvious to users. That lack of clarity is a governance failure, not just a design flaw.

In labs and industrial facilities, production environments sometimes run for weeks with temporary sensor bypasses, acknowledged or suppressed alarms because the underlying issue is “understood” and “being monitored”. The system looks normal even when safeguards are reduced, and redundant scenarios have already been activated. ISO 27001’s approach to continuous monitoring (A.8.16) and incident detection (A.5.24) assumes degraded or vulnerable states are visible to operators. In tightly coupled systems, however, these states must be particularly clear during stressful situations, as illustrated by Aeroflot Flight 593, where a subtle alert indicating partial autopilot disengagement was overlooked under pressure.

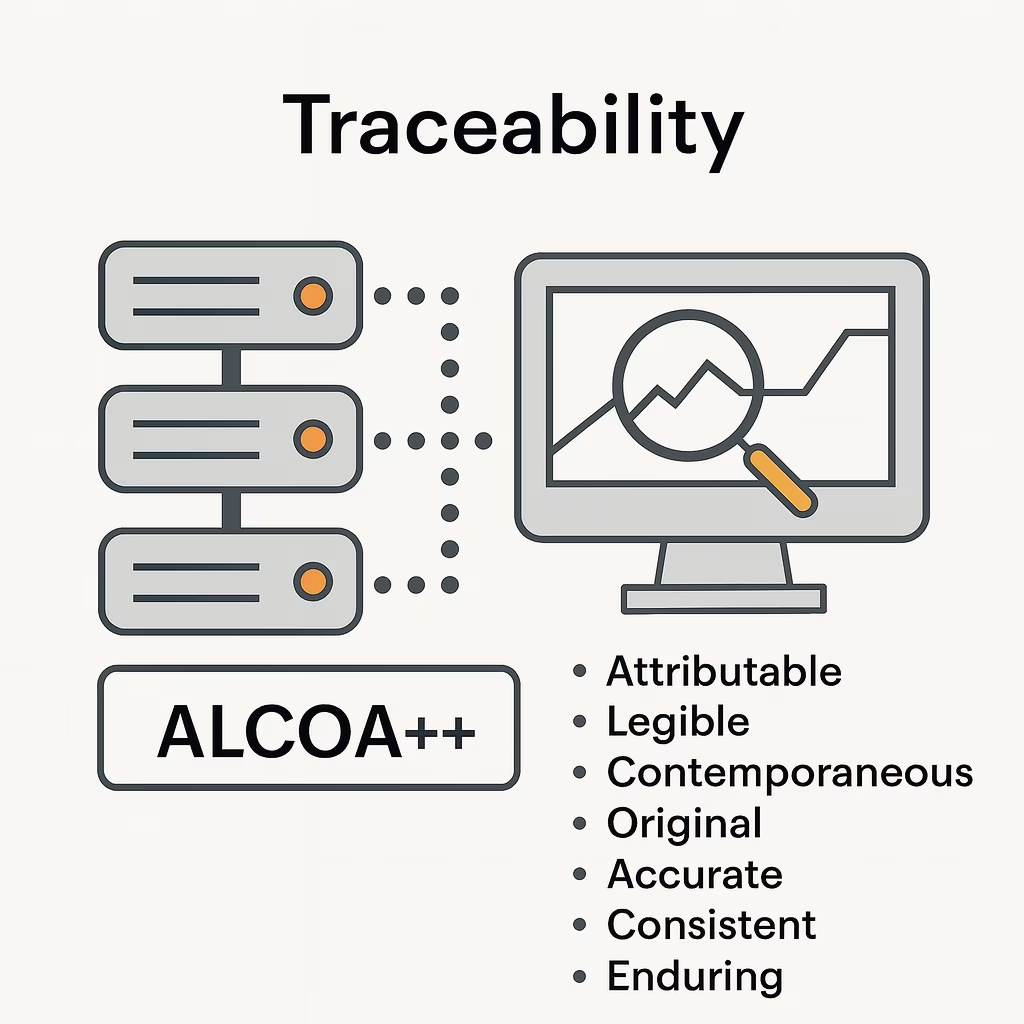

3) Treat traceability as a tool for real-time response, not just documentation

In Airframe, the investigation stalls because information is spread across organizations, not because it is hidden. Real systems fail in similar ways.

In pharmaceutical supply chains and industrial IT systems, answering basic questions — such as which software version was running, which dataset informed the decision, and who last changed a configuration — often requires reconstructing information across disconnected systems. Incident responses can stall not because data was deleted, but because it was distributed across vendor logs, internal monitoring systems, and operator handwritten records with no common timestamp or audit trail.

ISO 27001’s incident management controls (A.5.24-A.5.28) and ALCOA++ data integrity principles both assume that traceability should support the capacity for timely decision-making and response, not just post-incident forensics. Governance that treats traceability as mere documentation rather than an operational capability will consistently fail when it matters most.

4) Design for quick intervention, not perfect understanding

Plans and escalation rules should assume that people will not fully understand what is happening when something starts to go wrong. The ability to pause, isolate, or roll back actions can matter more than knowing the exact cause.

In batch release decisions or IT incidents, waiting for certainty can allow problems to escalate beyond control. ISO 22301’s business continuity requirements emphasize recovery time objectives; however, in tightly coupled systems, the ability to pause safely may be more important than the speed of resumption. Governance should protect the right to stop the system early, even when the diagnosis is not yet complete.

5) Learn without reverting to single-point attribution

After an incident, organizations are tempted to focus on the last mistake an individual made. That brings closure, but prevents nothing.

In regulated manufacturing and digital operations, incidents often reflect design choices made under time pressure, unclear information, or conflicting incentives. Learning improves only when organizations examine these broader conditions — not when they stop responsibility at the person closest to the failure.

Adopting these practices does not guarantee the prevention of all accidents. What they do influence is how honestly organizations face the systems they have built, and how responsibly they live with the risks that come with them.

Choosing to Live with Normal Accidents

Perrow’s argument removes a comforting fiction from governance: the belief that catastrophe is always evidence of individual failure. In tightly coupled, interactively complex systems, serious accidents are not exceptions. They are expressions of what the system is structurally capable of producing.

This has implications that extend beyond procedural compliance. When institutions choose to build and operate such systems, they are not merely managing risk; they are accepting foreseeable harm as a condition of normal operation. Governance responsibility, therefore, extends beyond compliance or post-incident accountability. It includes the decision to sustain architectures whose failure modes cannot be fully anticipated or arrested in time.

Perrow took this implication seriously. He argued that some systems — most notably nuclear power — should not be operated at all, or in a very limited capacity, because their normal accidents carry consequences that exceed acceptable social and political limits. For some, that judgment still holds.

What is notable is that the same reasoning is rarely applied to aviation. Commercial flights share the same system properties, yet are widely accepted. The difference is not architectural, but statistical and distributive: aviation’s normal accidents are rarer, and their consequences, while tragic, remain socially tolerable in aggregate. In practice, governance draws its boundary not at inevitability, but at frequency, scale, and the acceptability of harm.

Responsible governance, then, is less about control than custodianship. It requires owning the decision to operate systems whose failures will sometimes outrun human understanding and response. It demands visibility into coupling, automation, and efficiency pressures, and it resists the urge to attribute single-point blame when accidents occur.

Normal accidents cannot be eliminated from such systems. However, governance can decide whether their consequences are denied, normalized, or acknowledged and addressed meaningfully. That choice reflects institutional honesty about what has been built — and what society is willing to live with.