Chaos, Control, and the Limits of Prediction: Labatut's Warning for Technological Governance

When systems become sufficiently complex, prediction becomes unreliable. When dependencies deepen, control becomes an illusion. These aren’t theoretical propositions—they’re operational realities for anyone governing critical infrastructure, validating pharmaceutical systems, or managing industrial control networks, where emergent behavior routinely exceeds the assumptions built into safety cases and validation protocols.

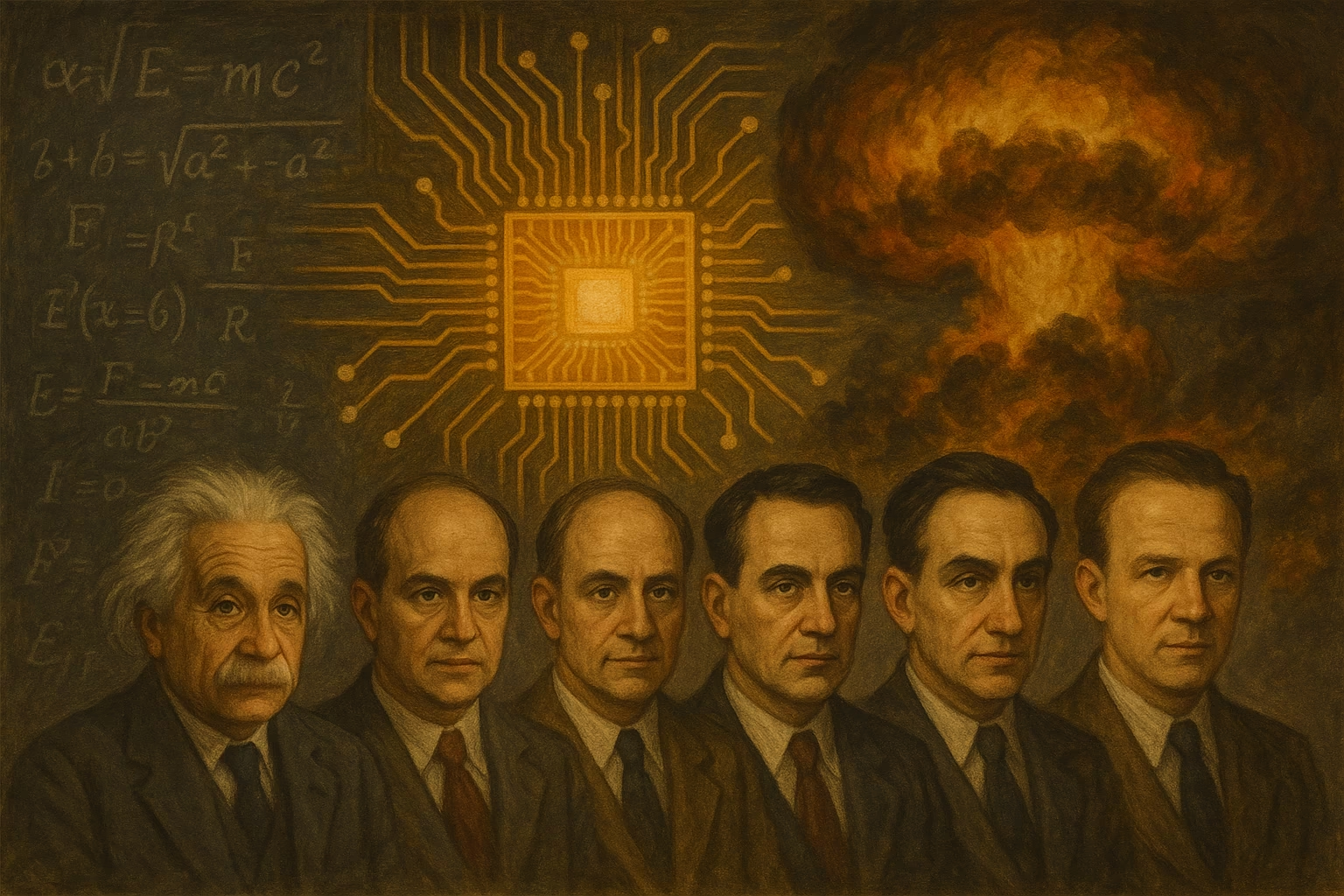

Benjamin Labatut’s The Maniac dramatizes this tension through the lives of 20th-century physicists who unlocked fundamental secrets of nature — and in doing so, created technologies whose behavior exceeds our capacity to predict or contain. The book poses an uncomfortable question for those who architect, govern, and hold accountability for complex cyber-physical systems: What happens when our fundamental notions about nature shift dramatically, and the new tools we acquire to extend control over it ultimately diminish our control over our physical surroundings and socio-political systems?

In The Maniac, Labatut delves into the paradox of technological progress — its capacity for both creation and destruction. He frames this exploration through the lens of Promethean hubris, portraying how visionary physicists like Albert Einstein, John von Neumann, Edward Teller, Enrico Fermi, and Werner Heisenberg not only unlocked the secrets of the universe but also disrupted the fragile systems that hold it together. Labatut suggests their breakthroughs have propelled humanity into a disquieting, uncharted era marked by both extraordinary powers and profound chaos.

The novel opens with the tragic story of Paul Ehrenfest, a Leiden physicist caught in the collapse of classical notions of harmony and order. Through his lover Nelly, Labatut reflects on the old belief that nature operated like a symphony — where disharmony was not only unthinkable but unspeakable:

If you discovered something disharmonious in nature… you should never speak of it… The harmony of nature was to be preserved above all things… To acknowledge even the possibility of the irrational… would place the fabric of existence at risk.

Quantum theory shatters this harmonious worldview, dragging science into uncertainty and irrationality. Labatut draws a provocative parallel between these scientific upheavals and the rise of irrational political movements in Europe, most notably Nazism. Overwhelmed by the dissolution of established structures and anticipating persecution, Ehrenfest succumbs to despair, taking his own life and that of his son with Down syndrome. His story becomes a harrowing metaphor for a world unmoored, where even the bedrock of scientific truth has become slippery and unstable.

Ehrenfest’s personal collapse is contrasted with John von Neumann’s embrace of chaos. One of the 20th century’s most influential minds, von Neumann is portrayed as almost superhuman in his ability to thrive in the face of complexity. He lays the mathematical foundations of quantum mechanics, pioneers game theory, develops the modern computer, and foresees artificial intelligence and self-reproducing machines. Where Ehrenfest saw a universe “riddled with chaos, infected by nonsense, and lacking any sort of meaningful intelligence,” von Neumann sees boundless potential.

While contemporaries like Oppenheimer wrestled with guilt over their destructive inventions — “If we physicists had already learned sin, with the hydrogen bomb, we knew damnation” — von Neumann remains untroubled. He insists humanity’s new tools could elevate it to “a higher version of ourselves, an image of what we could become.” For von Neumann, the old world is not worth mourning. Science and technology, he believes, must obliterate old boundaries to craft a new reality.

Labatut uses von Neumann’s character to probe deep moral and existential questions. Unlike his contemporaries, von Neumann embraces the unexpected and the irrational, recognizing that true innovation — and even intelligence — requires uncertainty and fallibility. Echoing Alan Turing, he foresees that machines must not only err but also exhibit randomness to achieve genuine intelligence:

If machines were ever to advance toward true intelligence, they would have to be fallible… capable not only of error and deviation from their original programming but also of random and even nonsensical behavior.

This unpredictability, von Neumann argues, is the foundation for “novel and unpredictable responses,” essential for intelligence that emerges rather than being programmed. He envisions machines that “grow, not be built,” capable of understanding language and “to play, like a child.” These chilling predictions resonate sharply today, as humanity grapples with the implications of AI systems that mimic human ingenuity but operate beyond our full control.

Governance Implications: When Systems Exceed Understanding

Von Neumann’s prophecy that “all processes that are stable we shall predict” and that “all processes that are unstable, we shall control” — captures a deeply held governance fantasy that persists today as the belief that sufficient monitoring, modeling, and intervention can tame the behavior of complex systems.

The Fallibility Paradox

Von Neumann’s insight that intelligence requires fallibility creates an uncomfortable implication for system governance: the moment we build systems sophisticated enough to adapt, learn, and respond creatively to novel situations, we simultaneously build systems whose behavior we cannot fully predict or constrain.

This paradox already manifests in the application of technological applications like machine learning and LLM usage today. When quality management systems incorporate machine learning for batch release decisions, or when manufacturing execution systems utilize predictive algorithms to optimize process parameters, we gain an adaptive capability — but sacrifice modern notions of complete determinism. The system may make better decisions on average while becoming less explicable in any individual case.

Governance frameworks, such as GxP and ISO 9001, assume that system behavior can be specified, validated, and maintained through change control. But as von Neumann recognized, systems capable of genuine learning must be “capable not only of error and deviation from their original programming but also of random and even nonsensical behavior.” How do you validate a system that is deliberately designed to behave unpredictably?

Control as Illusion

Labatut’s characters grapple with the consequences of unlocking power they cannot fully contain. One character reflects:

After all, when the divine reaches down to touch the Earth, it is not a happy meeting of opposites, a joyous union between matter and spirit. It is rape. A violent begetting.

This captures something essential about system design: the tools we build to extend control often create new vulnerabilities we cannot foresee. In critical infrastructure, automation and digital controls enhance efficiency and precision. But they also create pathways for cascading failures that move faster than human operators can comprehend or intervene.

Typical requirements for risk management and incident response assume organizations can identify, assess, and mitigate risks to network and information systems. However, when system components exhibit emergent behavior — when interactions between components produce outcomes that no individual component was designed to create — or when the introduction of large sub-systems alters the system as a whole, traditional risk assessment methods break down. You cannot assess the likelihood of states you cannot imagine.

The Epistemic Challenge

Ehrenfest’s despair stems from confronting a universe that refuses to behave according to comprehensible laws. For governance practitioners, a similar epistemological crisis looms: What do you do when the systems you’re responsible for exceed your capacity to understand them?

This isn’t theoretical. In pharmaceutical manufacturing, continuous processing systems create real-time dependencies between unit operations that traditional batch-based quality systems struggle to monitor. In industrial control networks, the interaction between IT security controls (such as network segmentation and access restrictions) and OT operational requirements (including real-time response and legacy protocols) creates failure modes that only appear under stress. In water treatment, the coupling between SCADA control systems, chemical dosing logic, and physical hydraulics can produce transient states that exist too briefly to capture but have lasting consequences.

Traditional governance assumes you can specify acceptable system states, monitor for deviations, and intervene before harm occurs. But in systems with high interactive complexity and tight coupling, unacceptable states may emerge and resolve faster than monitoring systems can detect them, or they may emerge from interactions between components that individually appear normal.

The Von Neumann Proposition

Von Neumann’s response to uncertainty wasn’t despair — it was acceleration. If we cannot predict system behavior, we build systems capable of predicting themselves. If we cannot control outcomes, we build systems capable of controlling their own evolution.

This logic drives current approaches to autonomous systems in critical infrastructure: machine learning models that detect anomalies in industrial control networks, AI-assisted incident response platforms, and predictive maintenance systems that learn equipment failure patterns. Each extends our governance reach — and each introduces new epistemic distance between system behavior and operator understanding.

The governance challenge isn’t whether to build these systems—we’re already building them. The challenge is how to govern systems whose sophistication exceeds our ability to specify their acceptable behavior in advance.

Conclusion: Governing the Ungovernable

Labatut draws the novel’s emotional force from the contrasting fates of Ehrenfest and von Neumann. In Ehrenfest, we see the despair of a man who cannot reconcile himself with a chaotic world. In von Neumann, we glimpse the exhilaration — and the alienating cost — of seeing the world as infinitely malleable.

The novel offers no easy answers—only the reminder that von Neumann’s confidence (“All processes that are unstable, we shall control”) may itself be the most dangerous form of hubris. Responsible governance begins not with the fantasy of total control, but with honest acknowledgment of its limits.

In environments where failure has both regulatory and operational consequences — such as pharmaceutical manufacturing, water treatment, energy distribution, and industrial control — this acknowledgment matters. It means designing systems that fail gracefully rather than catastrophically. It means maintaining human capacity to intervene even when we cannot fully understand the system state. It means preserving the ability to question whether what the system reports matches operational reality.

The Maniac is not merely a cautionary tale about scientific overreach; it’s a meditation on what it means to live in a world where the rules of existence can be rewritten. It compels readers to reflect on the limits of knowledge, the allure of god-like power, and the profound risks at the boundaries of what is possible. For those governing systems at those boundaries, Labatut’s warning resonates: the moment we stop questioning our capacity for control may be the moment we lose it entirely.