Information Control and Governance in Sealed Systems: Power Dynamics in Howey's Wool

When critical infrastructure operates in sealed environments — whether physical bunkers, regulatory silos, or air-gapped operational technology networks — information asymmetry can become a governance tool. Control over what operators see, what data flows between systems, and who interprets system states determines not just security posture but the fundamental power dynamics of the environment.

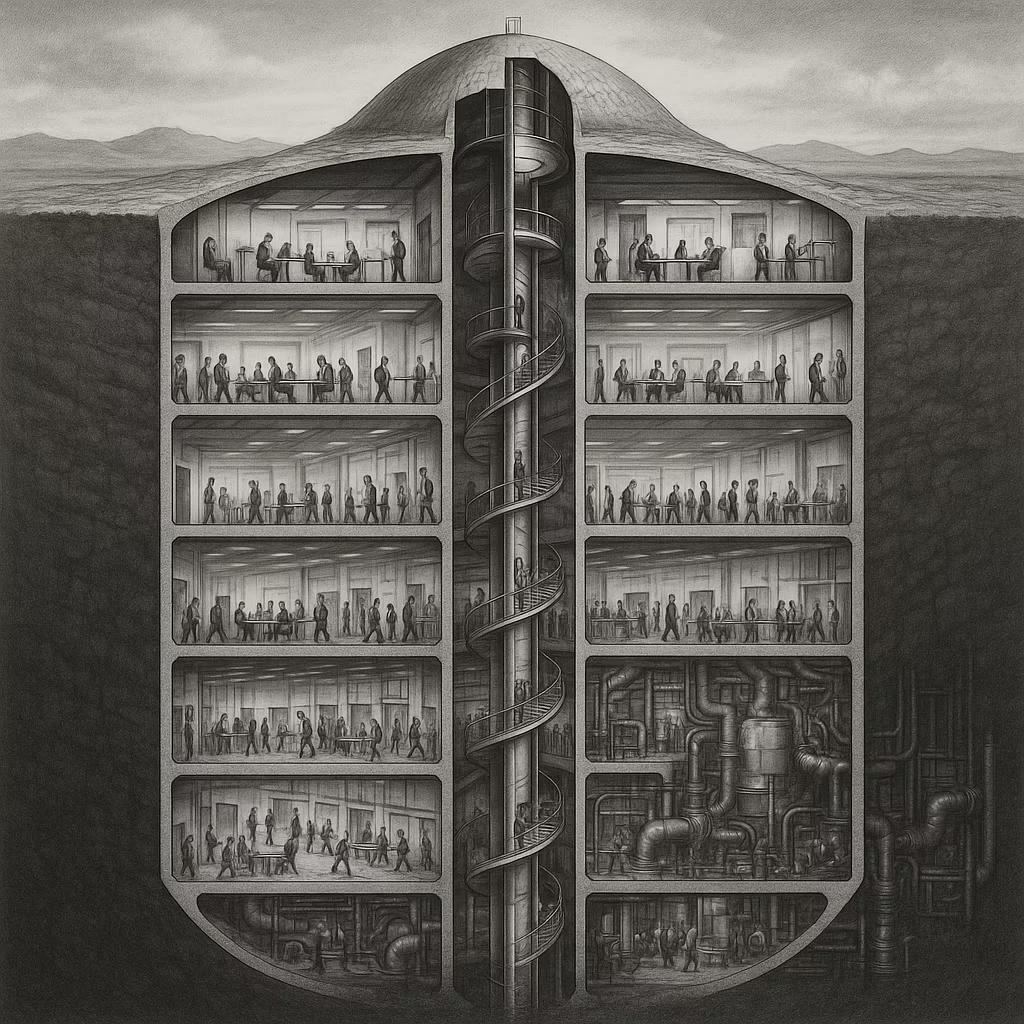

Hugh Howey’s Wool — the first book in the Silo trilogy — dramatizes this tension through a post-apocalyptic society living in an underground bunker where survival depends on maintaining sealed boundaries and controlling information about the outside world. While the premise is familiar to anyone who grew up during the Cold War or spent afternoons playing early Fallout games, Howey’s execution offers something more than genre exercise: a sustained examination of how sealed systems use information control to maintain governance authority, and why transparency mechanisms matter for operational resilience.

During my paternity leave, I watched Season 1 of the TV series Silo (available on Apple TV+ since May 2023). Captivated by its intriguing narrative, I decided to explore the source material to understand the systems dynamics the story revealed.

The basic conceit is instantly recognizable: nuclear catastrophe forces humanity underground into survival bunkers. What distinguishes Howey’s approach is not the premise but the variations he produces — the way physical and technical geography shapes corresponding political dynamics.

Similar to the in-your-face physical metaphor of the train in Snowpiercer, where the front carriages house the aristocracy and the back carriages hold the workers, the vertical structure of Howey’s silos gives material form to power relationships. But where Snowpiercer follows vulgar class warfare — producers in back, consumers in front — the silo’s conflict runs along a different axis: between technically skilled workers responsible for mechanical systems in the “down-deep” that generate the silo’s energy, and the IT department in mid-to-upper levels that uses that energy to exert control over information flows.

One class generates energy and is kept from information. The other controls information distribution and system visibility. This dynamic mirrors tensions familiar to those who operate physical systems and who often lack visibility into digital controls. In contrast, those managing information systems may not fully grasp their operational constraints.

Howey began the Silo series with a stand-alone short story published independently. After its success, he published subsequent chapters, later bundled as Wool. This publishing history is evident in the novel’s structure: a self-contained short story (42 pages), followed by a long chapter with new protagonists (90 pages), and then three longer chapters (97, 136, and 202 pages) featuring a single major protagonist. The switching of focalization works well as a narrative device, though the latter half loses some mystery and pacing when perspective stabilizes.

The original short story follows Holston, the Sheriff of Silo 18, as he investigates his wife Allison’s sudden request to step outside the silo to “clean” the camera lens—an act normally enforced as punishment for dissidents. Holston, embittered by grief, retraces Allison’s steps and discovers that she believed IT used sensors and cameras to deceive the population about the livability of the outside world. When Holston chooses to follow her and exits the silo, he sees a healthy, vibrant landscape through his helmet. When his air runs out, and he opens his visor, he confronts reality: he walks toward death in a nuclear wasteland. Both were deceived about the true nature of the outside world and IT’s control over perception.

This revelation — that what operators see through their interfaces may not reflect ground truth — resonates beyond fiction. In validated pharmaceutical systems, operators trust that LIMS data accurately represent sample results. In water treatment facilities, SCADA displays are assumed to reflect actual valve positions and chemical levels. When those assumptions break — whether through intentional manipulation, configuration drift, or simple display errors — the gap between interface and reality becomes a governance failure with operational consequences.

The second chapter follows Mayor Jahns and Deputy Marnes as they recruit Juliette, a skilled mechanic from the depths, as the new Sheriff. Juliette accepts on condition that she can conduct long-overdue mechanical maintenance requiring a power blackout. Bernard, Head of IT, opposes both the outage and Juliette’s appointment. He poisons Marnes’ canteen; the poisoning accidentally kills Jahns instead when she drinks from it.

The perspective then shifts to Juliette, who serves as the protagonist for the final three chapters. An intelligent and courageous young woman, Juliette’s analytical mind — honed by keeping machinery running — now uncovers the deep corruption behind Allison’s, Holston’s, and Jahns’ deaths. With help from allies in Mechanical, she discovers that IT designs cleaning suits for failure by using substandard heat tape and manipulates cleaners using augmented reality. Because cleaners experience the wasteland as a lush landscape through their helmet displays, they all want to share this “truth” with friends and family, motivating them to clean the camera. When Juliette is discovered, she’s sent to clean herself. The entire silo watches as she becomes the first person to refuse cleaning, walking over the hill toward the wider outside world.

The moments leading to Juliette’s cleaning and her walking out of camera view are deeply fulfilling. Having seen the TV series first, I anticipated these events — the last episode ends with Juliette surprised to be surviving, followed by a zoom-out revealing numerous craters suggesting near-infinite silos. Reading the book, I found the third chapter (“Wool: Casting Off”) would have made a near-perfect ending for the first book, with balanced pacing leading to a major plot climax.

What works for serialized chapter publication may not work for novel pacing. The fourth and fifth chapters, while expanding the world and revealing the wider silo network, lose the tight focus that made the earlier sections compelling. This is the only element keeping Wool from standing as a science fiction classic—a pacing issue stemming from its publication history rather than conceptual weakness.

Governance Implications: Sealed Systems and Information Control

Wool offers more than dystopian fiction — it provides a diagnostic framework for understanding governance challenges in sealed or tightly coupled environments where information control determines system behavior.

Information Asymmetry as Governance Tool In the silo, IT maintains authority not through force but through control over what people can see. The camera lens showing the outside world is the single interface between the sealed environment and external reality. By controlling that interface — including the augmented reality overlay in cleaning suits — IT controls collective understanding of the system’s purpose and constraints.

This pattern is commonly observed in operational environments where a small group controls system visibility, such as manufacturing execution systems where only certain roles can view batch genealogy, SCADA systems where field operators lack visibility into control logic, or compliance platforms where audit trails are accessible only to governance functions. Information asymmetry isn’t inherently problematic: role-based access serves legitimate purposes. But when visibility gaps prevent operators from detecting system degradation or anomalies, asymmetry can create the potential for fragility.

NIS2’s emphasis on “network and information systems security” (Art. 21) and business continuity planning assumes organizations can identify and manage dependencies across technical and operational boundaries. But sealed systems — whether physical silos or organizational ones — often make those dependencies invisible to the people who need to respond when things fail.

The IT/OT Boundary as Political Fault Line

Howey’s decision to place the silo’s central conflict at the IT/Mechanical boundary is structurally insightful. This isn’t arbitrary dystopian plotting — it reflects real tensions in environments where digital control systems overlay physical processes.

In pharmaceutical manufacturing, IT teams manage validated LIMS and MES platforms while operations teams run physical production processes. When system changes necessitate revalidation or when compliance controls restrict operational flexibility, those tensions arise. In water treatment, IT security teams implement network segmentation while operations teams need rapid access to SCADA interfaces during incidents. These aren’t conflicts between good and bad actors — they’re structural tensions between different system responsibilities operating under different constraints.

The silo’s governance failure isn’t that IT has power — it’s that no mechanism exists for Mechanical to challenge IT’s interpretation of system state, or to verify that the information they’re given reflects reality. When Juliette discovers the truth, she does so not through formal governance channels but through social engineering and technical investigation — the only paths available when official channels are sealed.

Transparency Mechanisms and resilience

Juliette’s survival depends on Mechanical workers secretly replacing the substandard heat tape in her cleaning suit with proper materials. This act of covert resilience — operators working around designed failure — is simultaneously a sign of system dysfunction and the only thing capable of saving her life.

In validated environments and critical infrastructure, similar dynamics emerge: operators develop workarounds when official procedures don’t align with operational reality, quality teams maintain “shadow” documentation when formal systems are too rigid, or engineers bypass safety interlocks they believe are misconfigured. These workarounds keep systems running but accumulate technical debt and increase risk. They emerge when official governance mechanisms lose legitimacy or fail to track system reality.

The silo’s ultimate fragility isn’t mechanical — it’s ontological and epistemological. When no one can verify IT’s claims about the outside world, and when challenging those claims is literally fatal, the system loses its capacity for course correction. resilience requires the ability to detect when assumptions are wrong and adjust accordingly. Sealed systems without transparency mechanisms cannot do this.

Conclusion: Governing What We Cannot See

Howey’s narrative architecture — moving from Sheriff to Mayor to Mechanic — traces a path from enforcement to political authority to operational reality. By the time we reach Juliette’s perspective, we understand that real governance authority in sealed systems rests not with titles but with those who maintain visibility into ground truth and have the technical competence to act on it.

For practitioners working in regulated or critical environments, Wool poses uncomfortable questions: What interfaces do your operators trust that might not reflect system reality? Where do information asymmetries create governance blind spots? Who has the authority to challenge interpretations of the system state when official channels appear to be compromised?

The silo’s tragedy isn’t that it sealed itself from the outside world — it’s that it sealed itself from internal truth. Governance in tightly coupled environments requires mechanisms for operators to verify, challenge, and correct their understanding of the system when evidence contradicts the official narrative. Without those mechanisms, sealed systems don’t just risk operational failure—they guarantee it.

Howey’s vivid imagery paints a bleak yet captivating picture of life within the silo, transporting readers into a confined world governed by technological control. Themes such as trust, deception, and the human will to survive resonate throughout the narrative, adding layers to the compelling story. His writing excels when he inhabits his characters’ perspectives: Juliette’s analytical rigor, Holston and Marnes’ grief, Lukas’ indecisiveness, and Bernard’s self-rationalization. Although some characters are short-lived, Howey uses inner dialogue to gradually expose the silo’s mysteries.

The novel’s later sections become less economical, particularly when describing Juliette’s technical work in Silo 17. The extended scene of draining flooded levels, while demonstrating her competence, adds little to the wider narrative and could have been tightened.

Despite uneven pacing in its latter portions, Wool stands out for its fresh take on post-apocalyptic survival, engaging characters, and sophisticated political dynamics. Through diverse and relatable characters, surprising revelations, and sustained attention to how information control shapes power, the novel illuminates governance challenges that extend well beyond its genre. Whether approached as a stand-alone reading or in conjunction with the successful TV adaptation of Silo, Wool represents a valuable addition to fiction that takes systems thinking seriously — worthy of exploration by practitioners and genre readers alike.