'The Maniac' by Benjamin Labatut is an inquiry into chaos, technological hubris, and modern physics’ transformative impact on the human condition

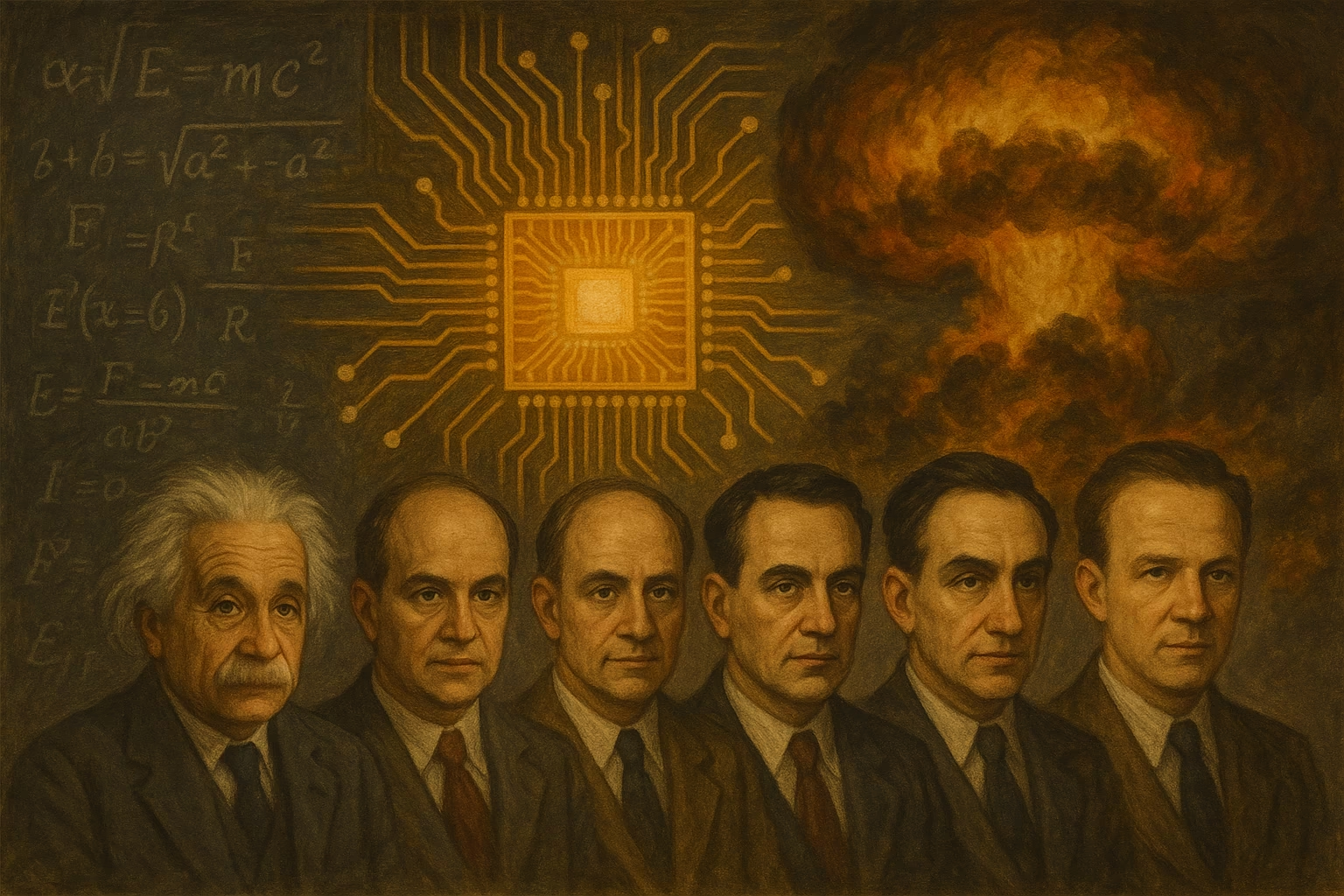

In The Maniac, Benjamin Labatut delves into the paradox of technological progress—its capacity for both creation and destruction. He frames this exploration through the lens of Promethean hubris, portraying how visionary physicists like Albert Einstein, John von Neumann, Edward Teller, Enrico Fermi, and Werner Heisenberg not only unlocked the secrets of the universe but also disrupted the fragile systems that hold it together. Labatut suggests their breakthroughs have propelled humanity into a disquieting, uncharted era marked by both extraordinary powers and profound chaos.

The novel opens with the tragic story of Paul Ehrenfest, a Leiden physicist caught in the collapse of classical notions of harmony and order. Through his lover Nelly, Labatut reflects on the old belief that nature operated like a symphony—where disharmony was not only unthinkable but unspeakable:

If you discovered something disharmonious in nature… you should never speak of it… The harmony of nature was to be preserved above all things… To acknowledge even the possibility of the irrational… would place the fabric of existence at risk.

Quantum theory shatters this harmonious worldview, dragging science into uncertainty and irrationality. Labatut draws a provocative parallel between these scientific upheavals and the rise of irrational political movements in Europe, most notably Nazism. Overwhelmed by the dissolution of established structures and anticipating persecution, Ehrenfest succumbs to despair, taking his own life and that of his son with Down syndrome. His story becomes a harrowing metaphor for a world unmoored, where even the bedrock of scientific truth has become slippery and unstable.

Ehrenfest’s personal collapse is contrasted with John von Neumann’s embrace of the chaos. One of the 20th century’s most influential minds, von Neumann is portrayed as almost superhuman in his ability to thrive amid complexity. He lays the mathematical foundations of quantum mechanics, pioneers game theory, develops the modern computer, and foresees artificial intelligence and self-reproducing machines. Where Ehrenfest saw a universe “riddled with chaos, infected by nonsense, and lacking any sort of meaningful intelligence,” von Neumann sees boundless potential.

While contemporaries like Oppenheimer wrestled with guilt over their destructive inventions— “If we physicists had already learned sin, with the hydrogen bomb, we knew damnation” —von Neumann remains untroubled. He insists humanity’s new tools could elevate it to “a higher version of ourselves, an image of what we could become.” For von Neumann, the old world is not worth mourning. Science and technology, he believes, must obliterate old boundaries to craft a new reality.

Labatut uses von Neumann’s character to probe deep moral and existential questions. Unlike his contemporaries, von Neumann embraces the unexpected and the irrational, recognizing that true innovation—and even intelligence—requires fallibility. Echoing Alan Turing, he foresees that machines must not only err but also exhibit randomness to achieve genuine intelligence:

If machines were ever to advance toward true intelligence, they would have to be fallible… capable not only of error and deviation from their original programming but also of random and even nonsensical behavior.

This unpredictability, von Neumann argues, is the foundation for “novel and unpredictable responses,” essential for intelligence that emerges rather than being programmed. He envisions machines that “grow, not be built,” capable of understanding language and “to play, like a child.” These chilling predictions resonate sharply today, as humanity grapples with the implications of AI systems that mimic human ingenuity but operate beyond our full control.

In The Maniac, Labatut weaves these narratives into a modern Promethean myth, warning against technological hubris. Just as Zeus punished Prometheus for stealing fire—a gift of forbidden knowledge—Labatut’s characters grapple with the consequences of unlocking power they are unprepared to wield. One character reflects:

After all, when the divine reaches down to touch the Earth, it is not a happy meeting of opposites, a joyous union between matter and spirit. It is rape. A violent begetting.

The novel prompts readers to confront the dual-edged nature of scientific progress: Does the pursuit of knowledge uplift humanity, or does it lead to its destruction—or possibly an enlightened destruction? Von Neumann’s chilling prediction echoes in this context:

All processes that are stable we shall predict. All processes that are unstable, we shall control.

But can humanity truly control the immense, unstable powers it has unleashed? Labatut leaves this question simmering, urging readers to consider the ethical costs of transcending natural boundaries.

Labatut draws the novel’s emotional force from the contrasting fates of Ehrenfest and von Neumann. In Ehrenfest, we see the despair of a man who cannot reconcile himself with a chaotic world. In von Neumann, we glimpse the exhilaration—and the alienating cost—of seeing the world as infinitely malleable. The Maniac is not merely a cautionary tale about scientific overreach; it’s a meditation on what it means to live in a world where the rules of existence can be rewritten. It compels readers to reflect on the limits of knowledge, the allure of god-like power, and the profound risks the boundaries of what is possible.