Political intrigue and human endurance inside a sealed society in Hugh Howey's 'Wool'

Spoiler Warning: This review contains detailed plot summaries and revelations from both the TV series ‘Silo’ and the novel ‘Wool.’ Proceed with caution if you want to avoid spoilers.

During my paternity leave, I indulged in season 1 of the TV series Silo, available on AppleTV+ since May 2023. Captivated by its intriguing narrative, I decided to explore the source material written by Hugh Howey to delve deeper into the story that had so engaged me.

The basic conceit of Wool - the first book in the Silo trilogy - is unoriginal and instantly recognizable for someone who grew up during the aftermath of the Cold War and spent many a free afternoon playing the early Fallout games energy blasting radscorpions and deathclaws. It can be formulated something like this: our nuclear flirtation has led to an apocalypse-level disaster, but thankfully, the parts of humanity that had enough foresight to be alarmed by the destructive potential of nuclear technology were able to survive the nuclear blast by burying themselves in nuclear bunkers.

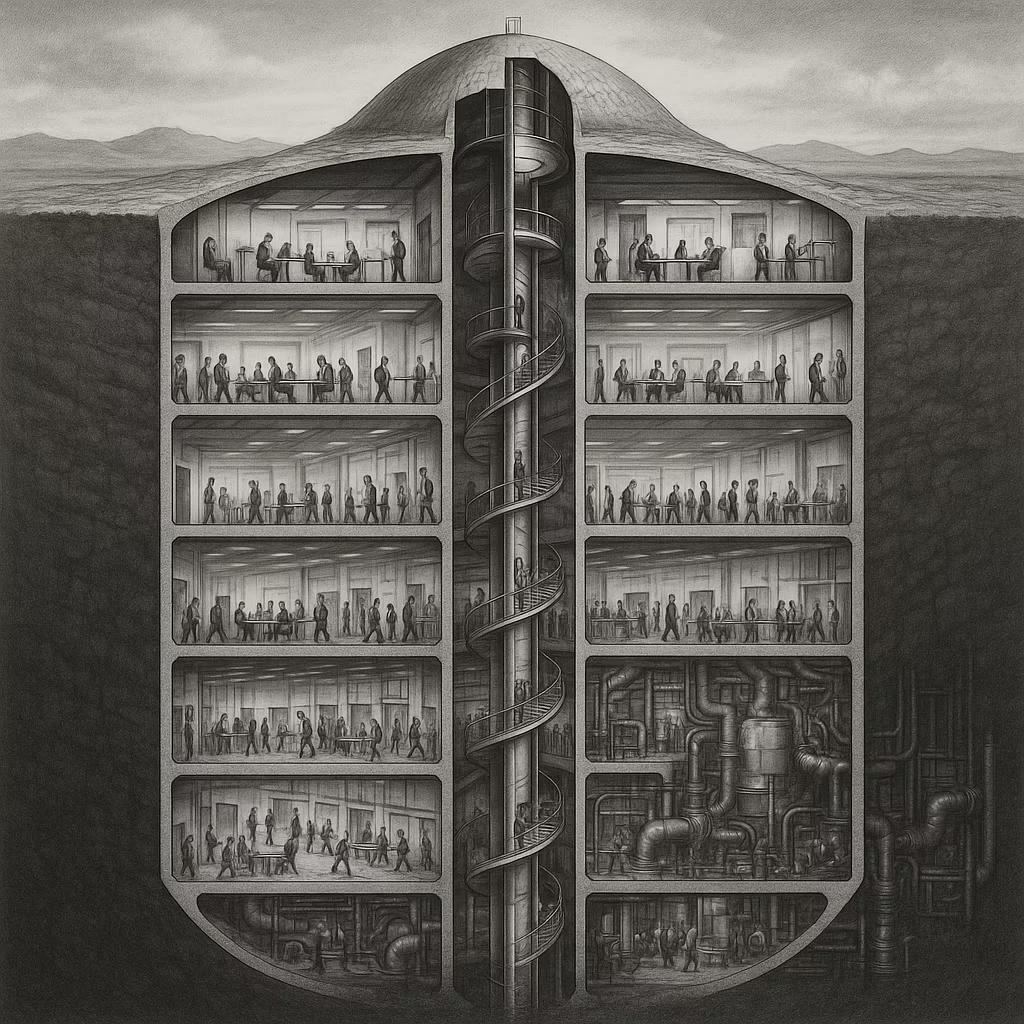

Although the conceit of a post-apocalyptic survivor society in a bunker or another confined space has been done previously, to varying levels of success, Howey’s take still manages to feel fresh. As anyone familiar with thought experiments knows: a thought experiment should be judged not by the quality of the conceit but by the quality and quantity of the variations one can produce. I’m looking at you: trolley problem. Similar to the in-your-face physical metaphor of the train in the ‘Snowpiercer’ series, where the front carriages were reserved for the aristocracy and the back carriages for the proles, the physical and technical geography of the ‘silos’ gives shape to a corresponding political dynamic.

In Snowpiercer, the physical hierarchy and -geography of the train that protects the last inhabitants of earth follows the lines of vulgar class warfare: the plebians/proles who produce take a seat in the back of the train, and the patricians/bourgeois who consume can sit in the front. The political dynamic in the silo is similar but different. Here the conflict is between the technically skilled artisans and workers responsible for the mechanical technology in the down-deep that is the lifeblood of the silo and the IT department that resides in the mid-to-upper levels that uses the energy generated in the down-deep to exert control over the population of the silo through information technology. One class generates energy and is kept from information, whereas the other exerts control over its use and the informational flow within the silo.

Howey began the Silo-series with a stand-alone short story that was published independently. After its success, he published subsequent chapters. These chapters were later bundled with the original short story as Wool - the novel. This publishing history is still visible in the novel’s narrative structure. The novel starts with a self-contained short story with one protagonist that is elegantly and economically written (42 pages), which is then followed by one long chapter with two new protagonists (90 pages), which in turn is followed by three even longer chapters (97, 136, and 202 pages) with one major protagonist. Although unusual, it does not impact the reading experience negatively. The switching of focalization works well as a narrative device, and if there is a criticism to be made, it may be that it is not used in the latter half of the book, which loses some of the mystery and pacing of the first part.

The original short story follows Holston, the Sheriff of Silo 18. He investigates his wife Allison’s sudden wish to step outside the silo to ‘clean’ the camera lens that provides a view of the outside world for the inhabitants of the upper levels of the silo, an act normally that is normally enforced as punishment for dissidents and criminals. Holston, embittered by grief, retraces his wife’s steps that led to the cleaning and finds that she was convinced that IT used their sensors and camera’s to deceive the population of the silo into thinking that the outside world was unlivable. She was convinced. He chooses to follow his wife and also asks to clean. When he exits the silo, he sees a healthy, vibrant world. When he runs out of air and opens up his visor, he is confronted with reality: he is walking toward his death in a nuclear wasteland. He and his wife were deceived about the true nature of the outside world and the control exerted by IT over the silo’s inhabitants’ perception of it.

The second chapter follows Mayor Jahns and Deputy Marnes, who embark on a trip deep down to recruit Juliette, their top candidate for Sherrif. Juliette agrees to take on the position of Sheriff on the condition that she be allowed to conduct long-overdue mechanical maintenance, which would require a power blackout to the silo. Jahns gives her consent to this arrangement. We soon discover Bernard, Head of IT, is enraged by the Mayor’s actions. He strongly opposes the power outage and Juliette’s appointment and poisons the canteen of Marnes. Instead of killing Marnes, the poisoning accidentally leads to the death of Jahns, who drinks from Marnes’ canteen on the way back up.

The POV then switches to Juliette, who will serve as our main protagonist for the final three chapters of the novel. Juliette, an intelligent and courageous young woman, emerges as a central figure who challenges the silo’s political order. Her analytical mind and dedication that kept the machinery running now uncover the deep-seated corruption within the silo leading to the tragic faith of Allison, Holston, and Jahns. With the help of her allies in Mechanical, she finds out that IT designs the cleaning suits for failure by using sub-par heat tape and manipulating those people sent out to clean using augmented reality technologies. Because cleaners experience the wasteland as a lush, green landscape, they all want to share this experience with friends and families. Juliette is soon found out by IT and is sent to clean herself. All the silo watches as Juliette is the first person who does not clean and walks over the hill of the silo’s crater towards the wider outside world.

The moments leading up to Juliette’s cleaning and her eventual walking out of view of the camera are deeply fulfilling. Remember: I saw the first season of the TV series first. The last episode ends with a close-up of Juliette, who is surprised to be surviving her ordeal, followed by the camera zooming out to a birds-eye shot of numerous craters, suggesting a near-infinite amount of silos. One cannot imagine a better cliffhanger to end a season. Reading the book, I anticipated these events and was eager to know which events and explanations would follow. That was the initial reason I set out to read the book. Looking back and comparing my reading and viewing experience, I now believe Wool, the novel, would have a near-perfect sci-fi plot with sufficient depth and ambiguity were it to have stopped somewhere near the point when the first season of the series stopped, namely after the third book ‘Wool: Casting Off’. It would have been a perfect first book of a series, with balanced pacing leading to a big plot climax in the third act.

What works for chapter-by-chapter publishing for an eager fanbase may not necessarily work for the pacing of a novel. This is a shame because the only thing that keeps me from regarding Wool as a sci-fi classic is the pacing of the fourth and fifth chapters of the novel.

Howey’s vivid imagery paints a bleak yet captivating picture of life within the silo, transporting readers into a confined world governed by technological control. Themes such as trust, deception, and the human will to survive resonate throughout the narrative, adding layers to the compelling story. His writing is at its best when empathizing with the narrative’s broad array of characters: from Julliett’s righteous, analytical mind, Holston and Marnes’ silent loving and grief, Lukas’ indecisiveness, and Bernard’s self-rationalization. The characters that are introduced are living beings who retain their hopes and dreams in the darkness of the silo. Although some of them are short-lived, Howey successfully manages to use the inner dialogue of his characters to expose the heart of the silo’s mystery gradually.

Howey’s writing is less economical and sometimes borders on tediousness, especially when describing the technical details Juliette concerns herself with in Silo 17. A specific case in point is the long, dragged-out scene where Juliette tries to drain the bottom levels of the empty silo with her companion Solo. This scene, which ultimately has no real purpose in the wider plot, could have been better thought out and may have well been had the novel been written as a self-contained piece of writing.

In conclusion, Wool stands out for its fresh take on a well-trodden genre, engaging characters, and intriguing political dynamics. Through a diverse and relatable cast of characters and surprising expositions, the novel unveils the mystery of the silos, keeping the reader entertained and intellectually stimulated. While the uneven pacing and needless detail in the latter part of the book do detract slightly from the overall reading experience, it doesn’t overshadow the novel’s core strengths. Howey’s blend of character-driven narrative, political intrigue, and meticulous world-building is further highlighted by the successful adaptation into the TV series Silo. Whether approached as a stand-alone reading experience or in conjunction with the series, Wool represents a worthwhile addition to the post-apocalyptic sci-fi genre. Despite minor flaws, it is worthy of exploration by both fans of the genre and newcomers alike.