How Paul Auster's 'City of Glass' uses the labyrinth of city life to explore grief and fragmented identity

The detective is one who looks, who listens, who moves through this morass of objects and events in search of the thought, the idea that will pull all these things together and make sense of them. In effect, the writer and the detective are interchangeable. The reader sees the world through the detective’s eyes, experiencing the proliferation of its details as if for the first time. He has become awake to the things around him, as if they might speak to him, as if, because of the attentiveness he now brings to them, they might begin to carry a meaning other than the simple fact of their existence.

My mother’s fiancé gifted me this book for my 35th birthday. While I knew Auster’s name and status as a modern master (he must’ve been mentioned in my Literary Studies courses at the University of Amsterdam), I hadn’t read his work. In recent years, the idea of reading a ‘postmodern masterpiece’ felt daunting. My earlier engagement with postmodern fiction, primarily through the meta-fiction of John Barth and David Foster Wallace, was intellectually invigorating but left me wary of the genre—it felt like a labyrinth that played tricks on the reader just for the sake of showing off. The prospect of diving into Paul Auster’s New York Trilogy seemed equally intimidating.

City of Glass surprised me. Unlike the self-referential intricacies of Barth or Wallace, it is a deeply sincere exploration of grief, identity, and the maddening maze of urban life. The novella’s tone is clear, its economy of language remarkable, and its hallmarks of postmodernism—intertextuality, the author’s implication in the plot, genre convention play, doubling, and mirroring of perspectives—feel intrinsic to its story rather than ostentatious flourishes. While its themes may not be groundbreaking, there is profound meaning in the connections Auster weaves, both within the narrative and to literary history.

The novella follows Daniel Quinn, an aspiring poet turned pulp fiction writer who copes with the loss of his wife and son by channeling his grief into detective stories under the pseudonym William Wilson. His isolated life is disrupted when he receives a late-night call intended for a private detective named Paul Auster. Intrigued by the mirroring of his own fiction, Quinn assumes Auster’s identity and takes the case.

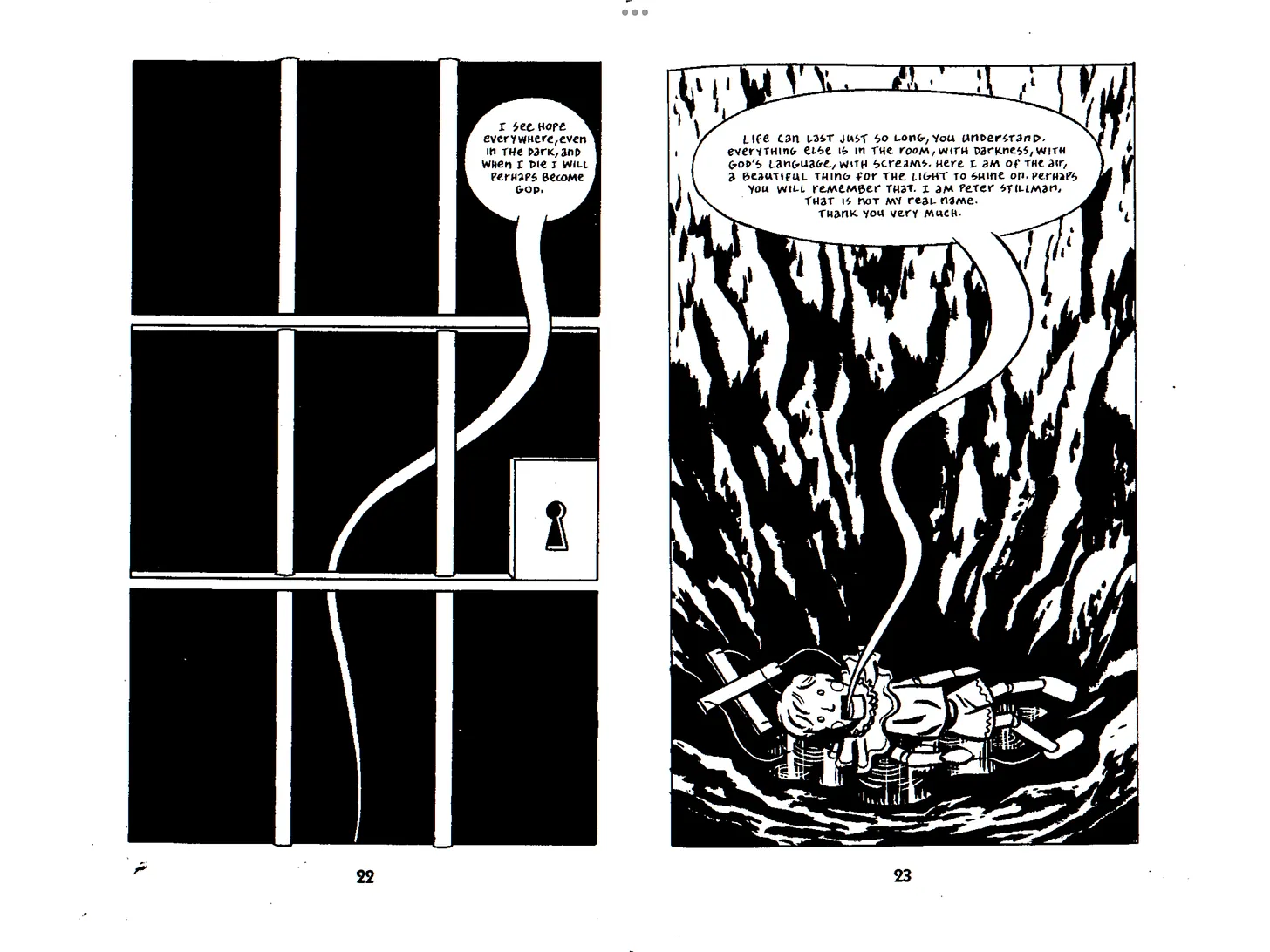

Caller Virginia Stillman hires “Auster” to protect her husband, Peter Stillman Jr., from his estranged father, Peter Stillman Sr. Stillman Jr. recounts the horrors of his childhood: his father, a deranged academic obsessed with discovering God’s primordial language, imprisoned him in a dark room for nine years, severing his access to language and the outside world. Now released from a mental institution, Stillman Sr. roams New York City, and his son fears a repeat of the past.

In the graphic novel adaptation of the novella by Karasik and Mazzucchelli, Stillman Jr. recounts his nine years in prison.

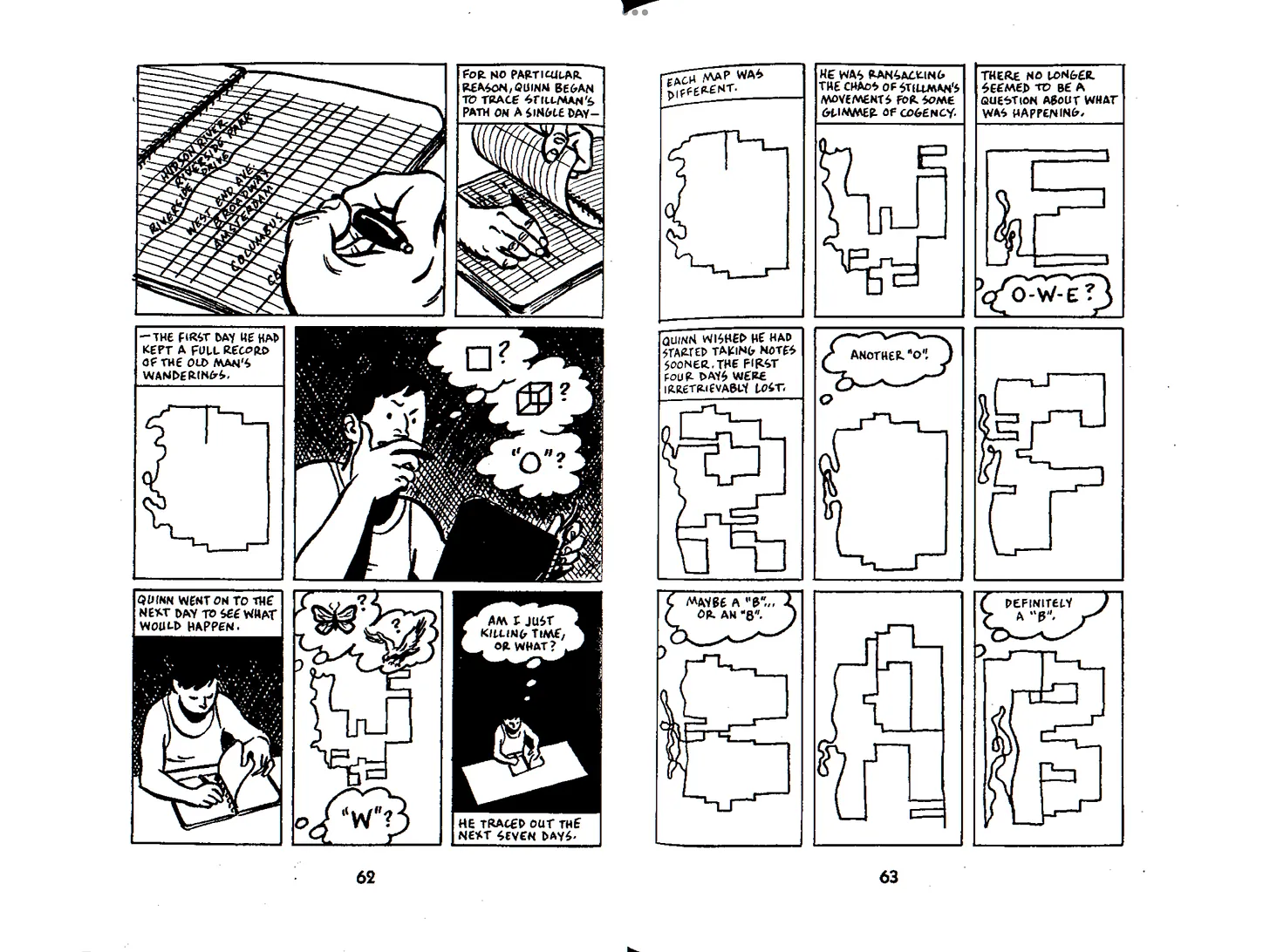

Quinn begins surveillance, tracking Stillman Sr. across the city as the elder man collects discarded objects on eccentric, maze-like walking routes. These routes, Quinn realizes, spell out “Tower of Babel,” a reference to Stillman Sr.’s belief in the fallenness of human language. Stillman’s behavior defies logic, but Quinn concludes that he has abandoned his cruel experiments with people for a quieter obsession with objects.

Quinn’s case grows stranger as he searches for the “real” Paul Auster and encounters an author by that name—who may or may not be the book’s author—researching the Stillman case. The narrative becomes layered with meta-narrative intrigue, blurring the lines between protagonist, narrator, and author. Like Cervantes’ Don Quijote, City of Glass constructs a story that is both an exploration of its characters and an examination of storytelling itself.

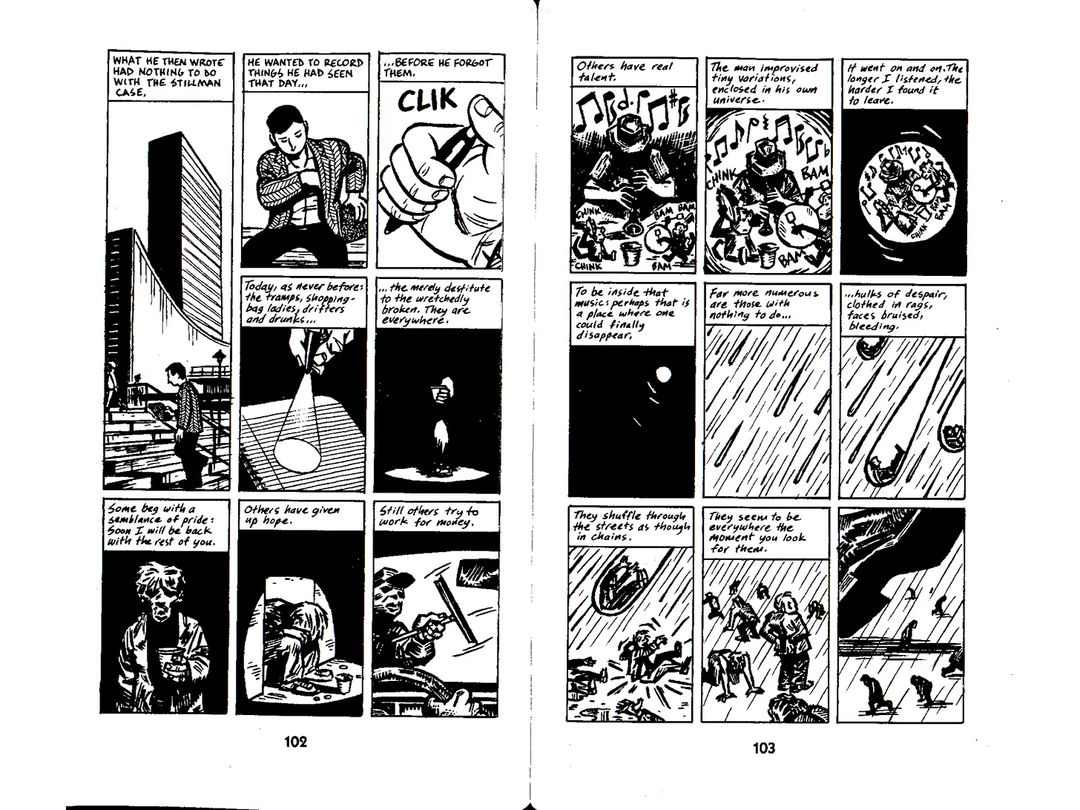

As Quinn becomes more entrenched in the case, his identity begins to fragment to the point of complete disassociation. He neglects his basic needs and descends into paranoia, living on the streets to surveil the Stillman home. His persona fractures into overlapping identities: William Wilson, the detective Paul Auster, and the broken man consumed by grief for his family. The boundaries between reality and fiction collapse entirely.

Auster deftly foreshadows Quinn’s fate with his descriptions of New York’s tramps and drifters—nameless figures who haunt the edges of the narrative. Like the city itself, Quinn becomes an infinite maze unto himself, chasing meaning that eludes him. Parallel to Peter Stillman Jr.’s years of confinement, Quinn’s five years of solitude as a bereaved writer manifest as a psychological prison. He is, ultimately, a man at odds with himself and the world.

Quinn had always thought of himself as a man who liked to be alone. For the past five years, in fact, he had actively sought it. But it was only now, as his life continued in the alley, that he began to understand the true nature of solitude. He had nothing to fall back on anymore but himself. And of all the thing he discovered during the days he was there, this was the one he did not double: that he was falling. What he did not understand, however, was this: in that he was falling, how could he be expected to catch himself as well? Was it possible to be at the top and at the bottom at the same time? It did not seem to make sense.

To fully appreciate the novel, I found myself retracing its steps, reading backward and forward, piecing together its fragmented layers. As the narrative dissolves into ambiguity, one interpretation becomes impossible to dismiss: the events are not “real” but a manifestation of Quinn’s grieving psyche. When Stillman Sr. identifies Quinn as his son, the language games reflect Quinn’s own attempt to reconcile his trauma. The novella’s conclusion, with Quinn scribbling sparse sentences in his red notebook, echoes his descent into silence—a desperate search for the primordial language of meaning and clarity, mirroring Eden’s prelapsarian unity.

Quinn no longer had any interest in himself. He wrote about the stars, the earth, his hopes for mankind. He felt that his words had been severed from him, that now they were a part of the world at large, as real and specific as a stone, or a lake, or a flower. They no longer had anything to do with him. He remembered the moment of his birth and how he had been pulled gently from his mother’s womb. He remembered the infinite kindnesses of the world and all the people he had ever loved. Nothing mattered now but the beauty of all this. He wanted to go on writing about it, and it pained him to know that this would not be possible. Nevertheless, he tried to face the end of the red notebook with courage. He wondered if he had it in him to write without a pen, if he could learn to speak instead, filling the darkness with his voice, speaking the words into the air, into the walls, into the city, even if the light never came back again. The last sentence of the red notebook reads: “What will happen when there are no more pages in the red notebook?

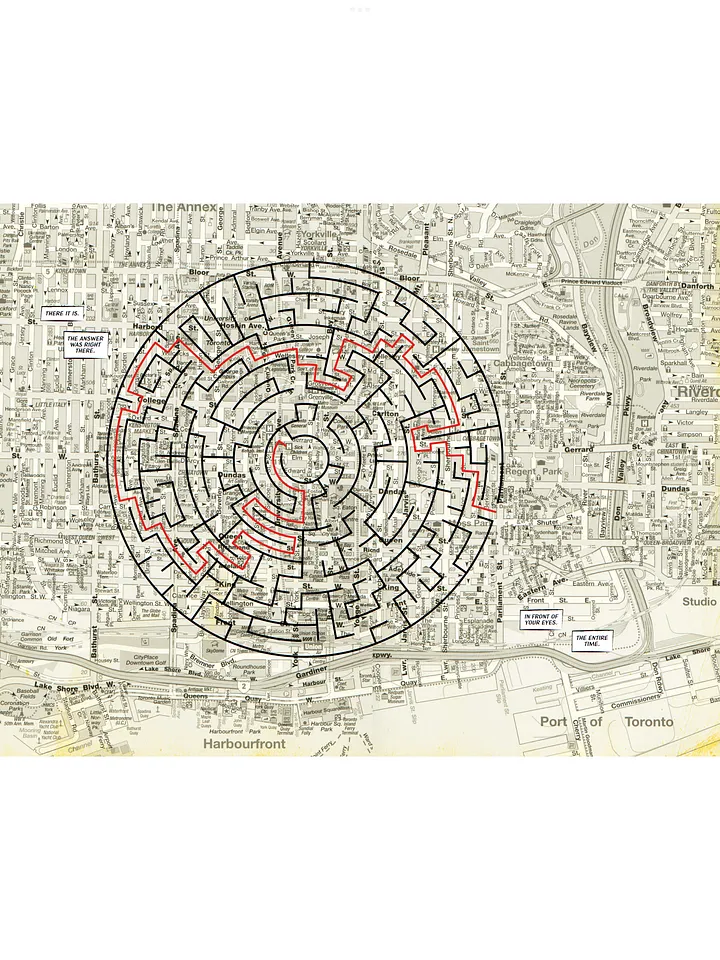

Reading Auster’s City of Glass alongside Jeff Lemire’s graphic novel Mazebook revealed striking parallels. Both works explore the labyrinthine nature of grief and urban life. While Quinn fades into obscurity, Lemire’s protagonist—a grieving father searching for his deceased daughter in a maze-like urban netherworld—finds a form of redemption. Lemire’s narrative even begins with a phone call, mirroring City of Glass. Yet unlike Auster, Lemire offers a hopeful path out of the maze. Grief and the city, while disorienting, become spaces for transformation.

In this way, Auster’s bleak labyrinth and Lemire’s redemptive maze form a compelling dialogue: a reflection of the shifting ways we navigate grief and identity in our ever-changing urban landscapes. Together, these works challenge us to confront the question: Is the maze a trap, or can it lead to escape? The answer, like the city itself, depends on where you stand and where you’re willing to go next.

One of the final scenes in Lemire’s Mazebook is when the protagonist finds his deceased daughter at the end of a maze-like netherworld.